Hot Wheels and Angst in Metropolis II

Evan Moffitt

4/14/2012

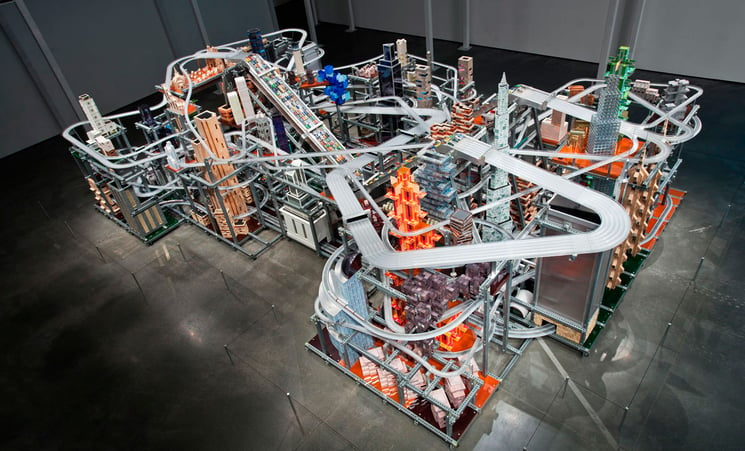

If you spend enough time with Metropolis II (2011), the din

starts to wear you down. Chris Burden’s massive kinetic sculpture, on view in

the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA since January, buzzes with the friction of 400,000

plastic wheels against 18 roadways and a six-lane freeway. Viewed from the side

or above from a catwalk, Metropolis II is a dense tangle of steel beams that

support constant motion. Like a packed metropolis, the sculpture is a reminder

of the modern city’s constant noise and activity, and the stress that accompany

them.

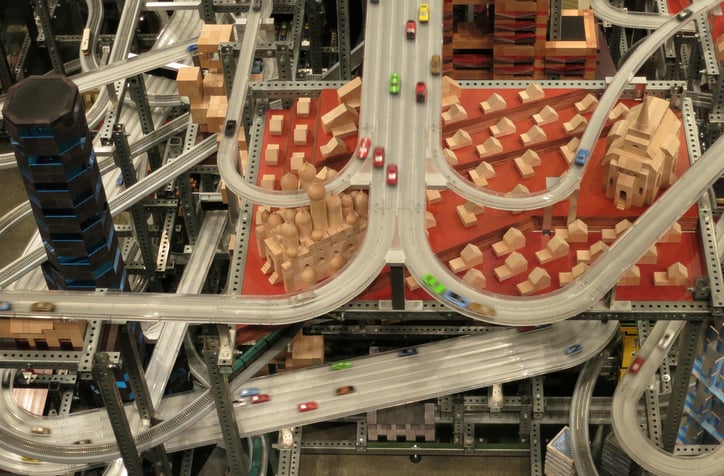

As I circled Burden’s city, I found myself confronted by a

fantasy of architectural pastiches—an Erector Set Eiffel Tower in company with

a wood-block Taj Mahal—circled by roadways with Burden’s self-made Hot Wheels

cars, racing dangerously at 240 scale miles per hour. I was looking at a

child’s dream, designed and constructed with exacting detail. Burden’s

stylistic hodgepodge came off as masturbatory: the artist, as God, constructs a

perilous and intricate world in which he places postcard monuments from a toy

View-Finder.