Northwest x Northwest: Seattle and the Hypercube

Evan Moffitt

4/14/2013

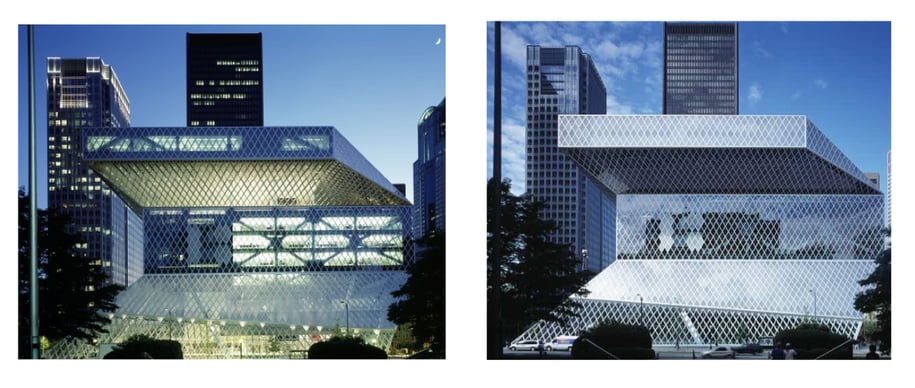

Nestled into the slope of 4th Street, is Seattle’s Central Library a glistening crystalline geometric projection. Just blocks from Pike’s Place Market, where tourists flock to Starbucks’ flagship store and peruse boutique confectionaries, is the country’s most architecturally progressive library; a vision for design enthusiasts and bibliophiles alike. The Central Library, designed by Rem Koolhaas and Seattleite Joshua Ramus, opened its doors in 2004, nearly doubling the stacks’ capacity and heralding the digital age with 400 computers and wireless Internet.

Most remarkable about the Central Library, however, is its form: tessellated cubes of reading rooms and computer labs, lacquered in thick black paint, are nestled within a latticework of steel and glass. The exterior grid pitches precariously forward at its upper floors, and sharply backwards at its base, expressing tangible structural tension on its visitors as they nonchalantly flip through the daily newspaper. The library’s guests sit above a semi-transparent vortex, a pyramidal atrium surrounding the library’s middle floors, formed by the shifted base and observatory level. The building’s integrity shifts beneath their very feet, and threatens to collapse above shaded pedestrians on the hilly streets below. Koolhaas’ airy geometry recalls a hypercube – a cube projected beyond the third dimension. As a treasure trove of timeless relics, a library projects conceptually into the fourth dimension, even as its structural presence remains resolutely in the third.

I found myself in the Central Library after a visit to the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) just down the street. SAM recently acquired fifty works of art from the Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection, an assembly of seminal Minimalist and Conceptual works. Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, are New York City natives who began amassing a sizeable collection in 1962, donated most of their contemporary pieces to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. The remaining pieces were disbursed to fifty museums in fifty states, Washington state’s fifty allotted works donated entirely to the Seattle Art Museum.

The works from the Vogel Collection will be on view until June 30th, on the museum’s third floor, hanging from brightly painted yellow and orange walls, which liven the somber palette of work from artists like Alain Kirilli and Sol LeWitt. It is LeWitt’s work in particular (displayed in the center of the gallery) that recalls the nearby Central Library. LeWitt’s 1, 2, 3, 4 (1980-1983), an intricate white tesseract of painted balsa wood, is unfolds its structural grid much like the pitched floors of Koolhaas’s library. Even thirty years later, such projected geometry insists on mathematical and scientific influence in the furthering of Modernist design and artistic production. A progressive Northwestern city like Seattle, where Boeing and Microsoft engineer digital age, is fertile soil for that Modernism to take root and flower, unfolding its petals like a cube of infinite dimension.