The potent 'Tea and Morphine'

Jesy Odio

2/19/2014

In a room with mute salmon-colored walls, above an array of prints, reads a quote emblazoned in gold from Gustave Flaubert’s debut novel, Madame Bovary: “She wanted to die, but she also wanted to live in Paris”—a fitting line to decorate the Hammer Museum’s exhibition, Tea & Morphine: Women in Paris, 1880 to 1914. Most of the pieces on display depict women very much like Flaubert’s Emma Bovary: French women searching for a means to alleviate their urban ennui.

Tea & Morphine draws the majority of its works from the Elisabeth Dean Collection of French prints, as well as holdings from the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. Most of the works portraying women in a state of drug-induced euphoria are prints made by male artists, with the exception of Mary Cassatt. Among the many prints of a total of 43 artists, there are some literary hidden gems from the fin-de-siècle writers throughout the exhibition.

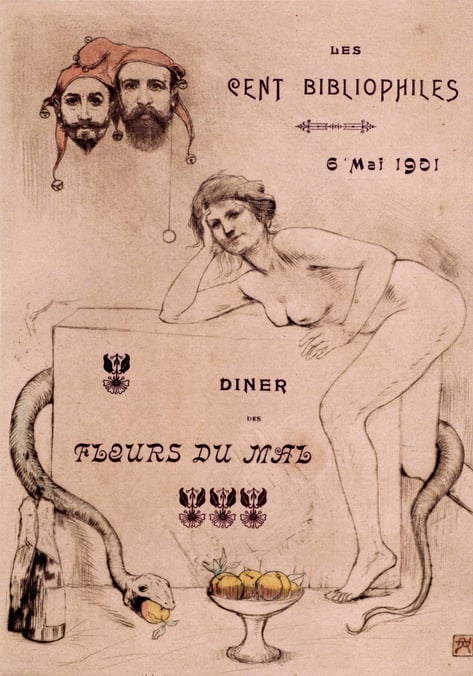

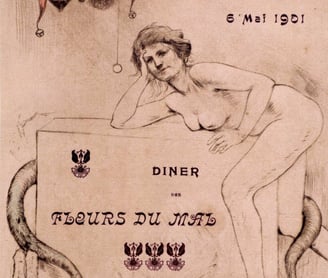

During an intimate walkthrough of the exhibition, curator Victoria Dailey pointed to an advertisement for an edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal by Armand Rassenfosse, noting that “Just the title of Fleurs du Mal influenced so much of later art because there was always this association of flowers, women, and evil. Much of the intellectual underpinnings come from Baudelaire, and his writings, and his poetry”. The references to Baudelaire’s work are plentiful as most of the works are garlanded with flora and fauna. For instance, in Georges de Feure’s La Source du Mal (The Source of Evil), a naked woman lying in a meadow, adjacent to a vulvar iris, sheds a stream of bloody tears.

Armand Rassenfosse

Les Cent Bibliophiles, diner des fleurs du mal, 1901

Color Etching

“Keep in mind that a lot of these works that are now on the wall were not conceived to have ever been framed and on public display,” said Dailey as she walked through one of the four galleries in the exhibit, which feels more like a storybook than a museum display. “Prints were often aligned with writers, because oftentimes prints were used to illustrate books,” co-curator Cynthia Burlingham chimed in; “there’s an interesting connection between words and prints.”

Amid works of women suffering wild cases of addictive hysteria, one reoccurring topic is leisurely reading. Despite how big of a fanatic fan I am of prints depicting the fantastic world of the Parisian demimonde, I could not identify with many of the modern Parisian women. Instead, I found myself drawn to two prints that portrayed the quiet stillness of women in a domestic setting. Two prints with the same title, La Lecture (The Reading), and two prints which, in plain sight, dramatize the developing presence of literature in late 19th century French society. Francis Jourdain’s color etching depicts an angelic young lady with porcelain skin in an all-encompassing golden dress holding a book. In Georges Jeanniot’s version, a dark-haired woman sits upright and reads to a young lady, as she lies across a couch with her blonde hair loose and free-flowing.

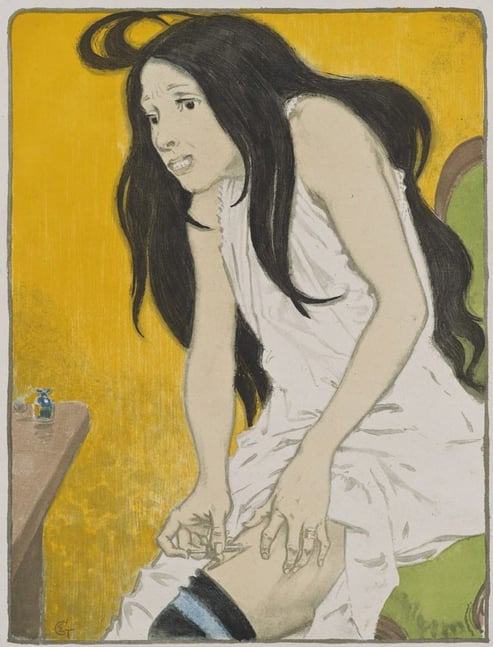

Eugene GrassetLa Morphinomane (The Morphine Addict), 1897 Color etching

Tucked in the last room, words heavy with meaning but discretely painted can be found on one of the few prints depicting the countryside. Vertically printed along the side of a portrait of a provincial girl with a scarf wrapped around her head is a line from Victor Hugo’s poem, L’Enfant: “Je veux de la poudre et des balles” (“I want gunpowder and bullets”).

In the bohemian world of the mystical Tea and Morphine exhibition, a look at the emergence of Symbolist art uncovers the deep connection between French printmaking and literature. The lonely anguish of Parisian women that so preoccupied writers of the Belle Époque is captured beautifully in this charming collection.